From all the compression methods available, Zip is probably one of the most popular ones.

Released in 1989 by Philip Katz, Zip is widely used by system administrators in order to reduce the size of bulky files and directories on your system.

Nowadays, Zip is available on all operating systems on the market : whether it is Windows, Linux or MacOS.

With zip, you can easily transfer files between operating systems and save space on your disks.

In this tutorial, we are going to see how you can easily zip folders and directories on Linux using the zip command.

Zip Folder using zip

The easiest way to zip a folder on Linux is to use the “zip” command with the “-r” option and specify the file of your archive as well as the folders to be added to your zip file.

You can also specify multiple folders if you want to have multiple directories compressed in your zip file.

$ zip -r <output_file> <folder_1> <folder_2> ... <folder_n>

For example, let’s say that you want to archive a folder named “Documents” in a zip file named “temp.zip”.

In order to achieve that, you would run the following command

$ zip -r temp.zip Documents

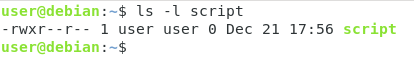

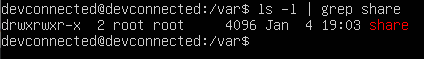

In order to check if your zip file was created, you can run the “ls” command and look for your archive file.

$ ls -l | grep .zip

Alternatively, if you are not sure where you stored your zip files before, you can search for files using the find command

$ find / -name *.zip 2> /dev/null

Zip Folder using find

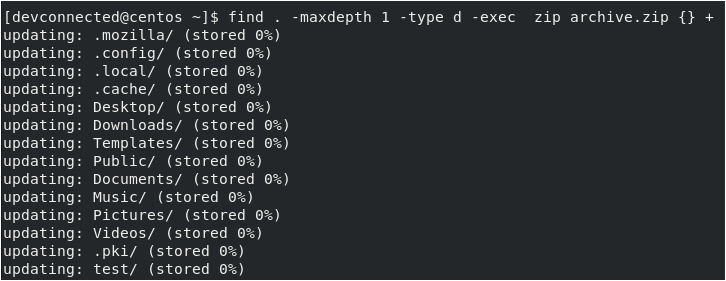

Another great way of creating a zip file for your folders is to use the “find” command on Linux. You have to link it to the “exec” option in order to execute the “zip” command that creates an archive.

If you want to zip folders in the current working directory, you would run the following command

$ find . -maxdepth 1 -type d -exec zip archive.zip {} +

Using this technique is quite useful : you can choose to archive folders recursively or to have only a certain level of folders zipped in your archive.

- How To Zip Multiple Files on Linux

- How To Encrypt File on Linux

- How to Move Files and Directories in Linux with mv Command

Zip Folder using Desktop Interface

If you are using GNOME or KDE, there’s also an option for you to zip your folders easily.

Compress Folders using KDE Dolphin

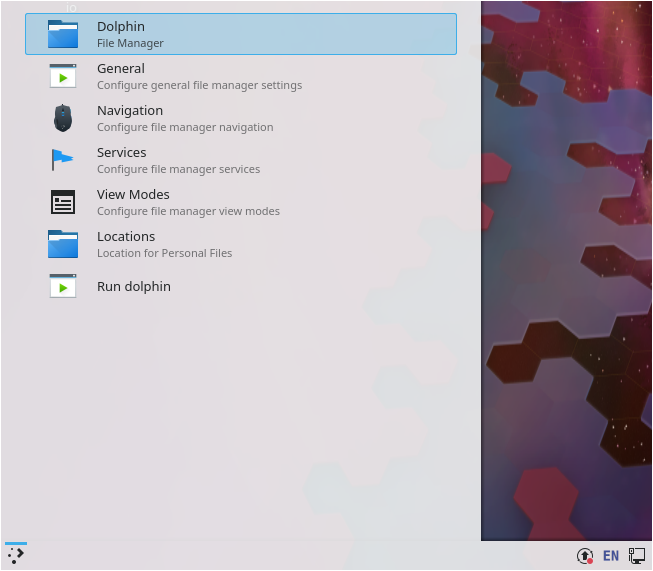

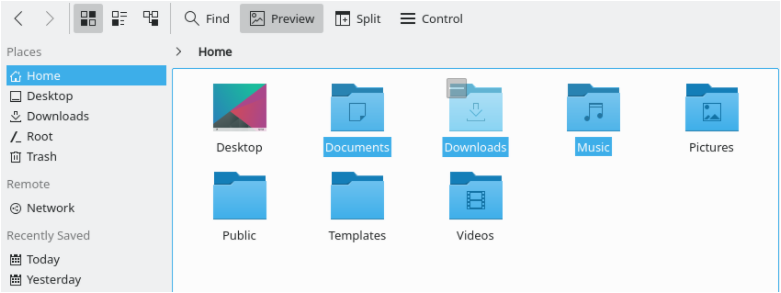

If you are using the KDE Graphical Interface, you will be able to navigate your folders using the Dolphin File Manager.

In order to open Dolphin, click on your the “Application Launcher” button at the bottom left of your screen and type “Dolphin“.

Click on the “Dolphin – File Manager” option.

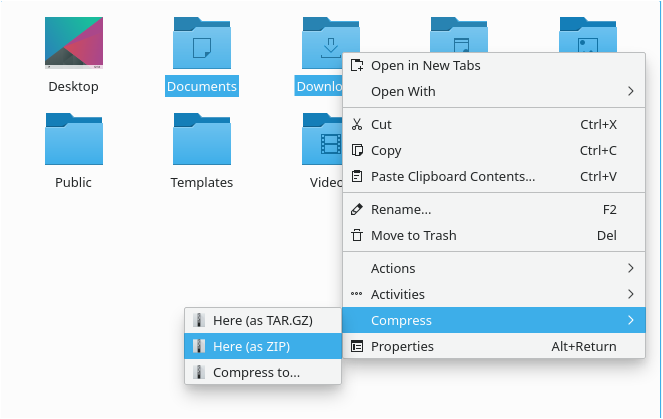

Now that Dolphin is open, select the folders to be zipped by holding the “Control” key and left-clicking on the folders to be compressed together.

Now that folders are selected, right-click wherever you want and select the “Compress” option.

When hovering your mouse cursor over the “Compress” option and select the “Here (as ZIP)” option in the menu.

If you want to zip folders in another location, you will have to select the “Compress to” option, specify the location and the compression mode (as ZIP).

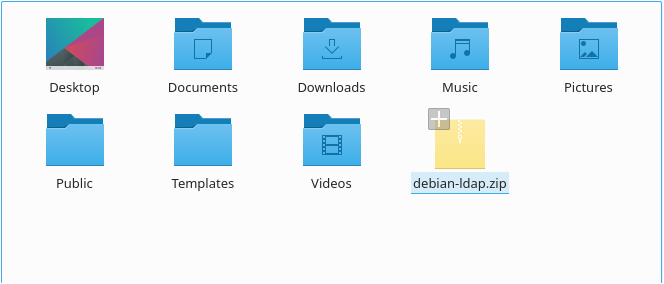

After a quick time, depending on the size of your archive, your zip should be created with all the folders you have selected in it.

Congratulations, you successfully created a zip for your folders on Linux!

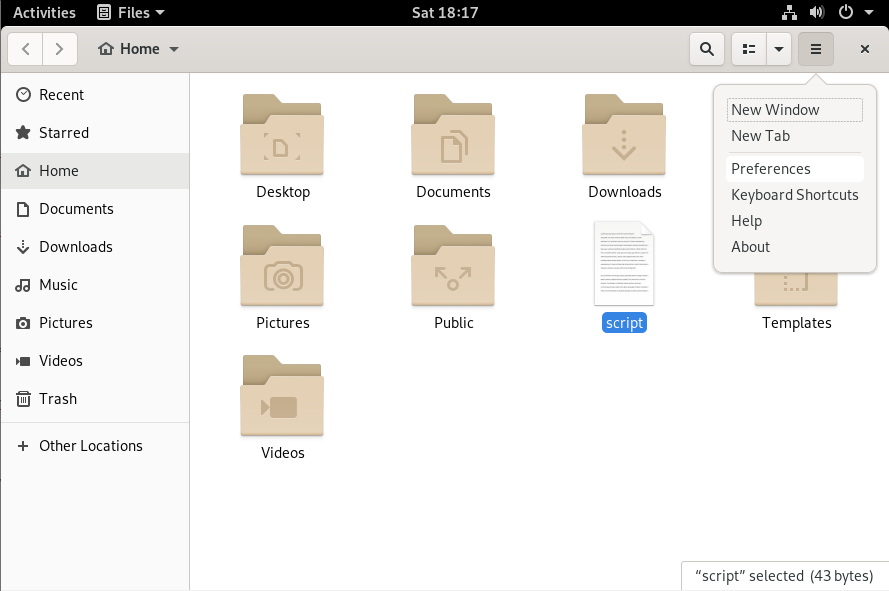

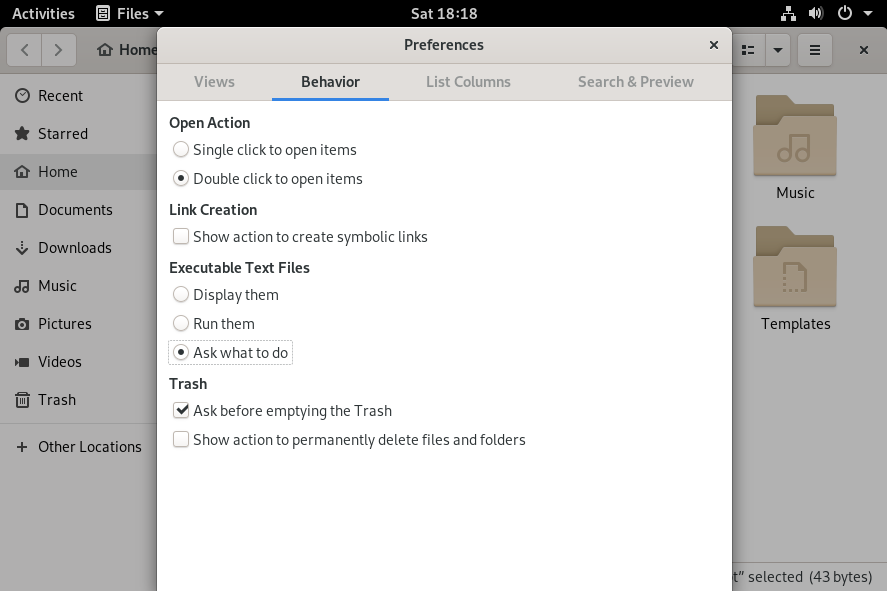

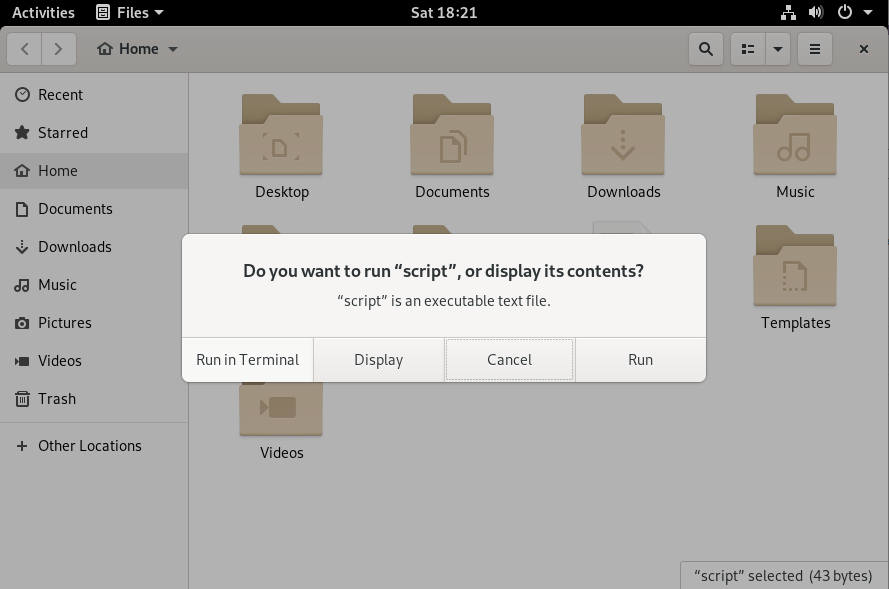

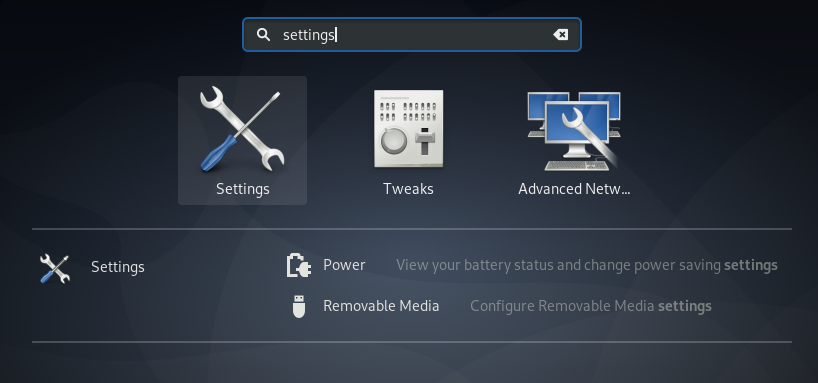

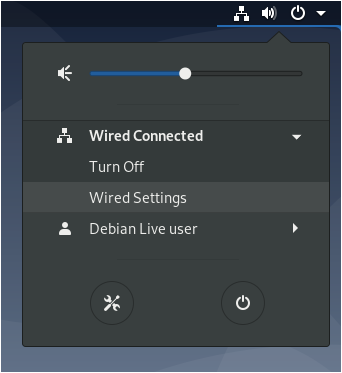

Compress Folders on GNOME

If you are using GNOME, on Debian 10 or on CentOS 8 for example, you will also be able to compress your files directly from the user interface.

Select the “Applications” menu at the top left corner of your Desktop, and search for “Files“

Select the “Files” option : your file explorer should start automatically.

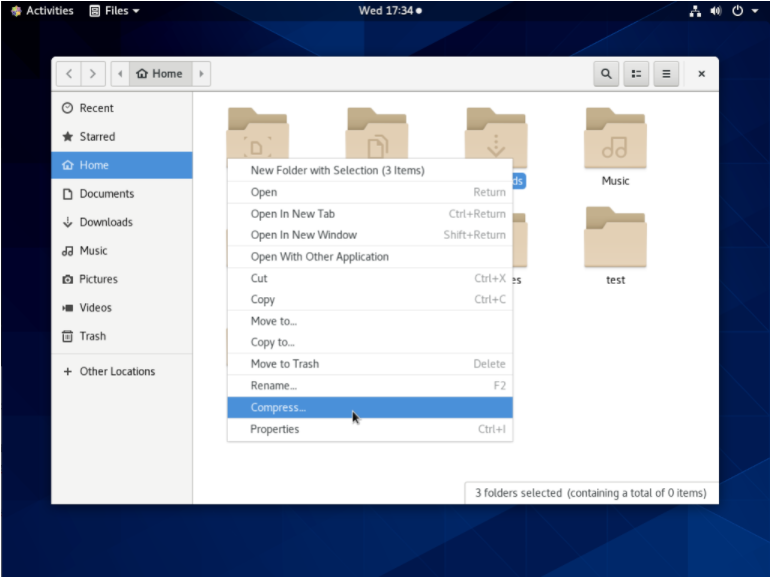

Now that you are in your file explorer, select multiple folders by holding the “Control” key and left-clicking on all the folders to be zipped.

When you are done, right-click and select the “Compress” option.

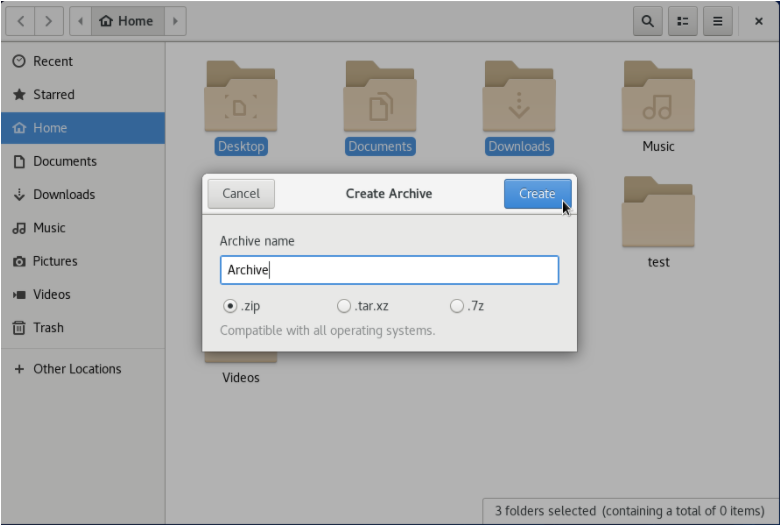

Now that the “Compress” option is selected, a popup window should appear asking for the filename of your zip as well as the extension to be used.

When you are done, simply click the “Create” option for your zip file to be created.

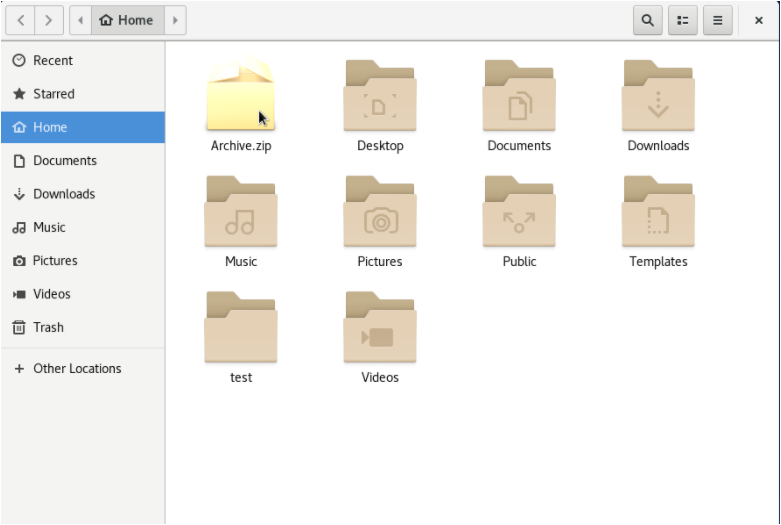

That’s it!

Your folders should now be zipped in an archive file : you can start sending the archive or extracting the files that are contained in it.

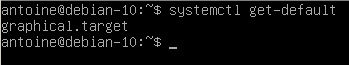

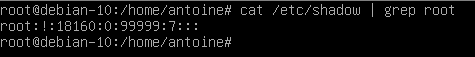

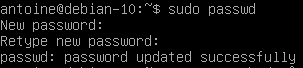

Zipping Directories using Bash

In some cases, you may not have a graphical interface directly installed on your server.

As a consequence, you may want to zip folders directly from the command-line, using the Bash programming language.

If you are not sure about Bash, here’s a Bash beginners guide and another one for more advanced Bash scripting.

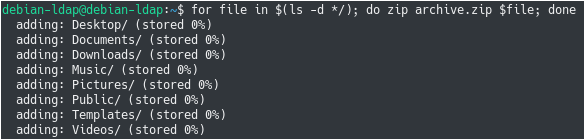

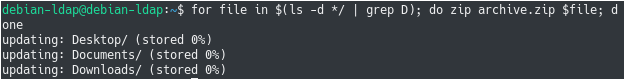

In order to zip folders using Bash, use the “for” loop and iterate over the directories of the current working directory

$ for file in $(ls -d */); do zip archive.zip $file; done

Using bash, you can actually get specific when it comes to the folders to be zipped.

For example, if you want to zip folders beginning with the letter D, you can write the following command

$ for file in $(ls -d */ | grep D); do zip archive.zip $file; done

Congratulations, you successfully created a zip for your folders in the current working directory!

Conclusion

In this tutorial, you learnt how you can easily create zip files for your folders on Linux.

You learnt that it is either possible to do it using the command-line and commands such as zip, find or the Bash programming language.

If you are using a graphical interface (such as KDE or GNOME), you can also zip folders by navigating the file explorer and right-clicking on the folders you are interested in.

If you are interested in Linux System Administration and quick tips, we have a complete section dedicated to it on the website, so make sure to check it out!