In Linux, it’s very often to execute Input or output redirection while working daily. It is one of the core concepts of Unix-based systems also it is utilized as a way to improve programmer productivity amazingly.

In this tutorial, we will be discussing in detail regarding the standard input/output redirections on Linux. Mostly, Unix system commands take input from your terminal and send the resultant output back to your terminal.

Moreover, this guide will reflect on the design of the Linux kernel on files as well as the way processes work for having a deep and complete understanding of what input & output redirection is.

Do Check:

If you follow this Input Output Redirection on Linux Explained Tutorial until the end, then you will be having a good grip on the concepts like What file descriptors are and how they related to standard inputs and outputs, How to check standard inputs and outputs for a given process on Linux, How to redirect standard input and output on Linux, and How to use pipelines to chain inputs and outputs for long commands;

So without further ado, let’s take a look at what file descriptors are and how files are conceptualized by the Linux kernel.

Get Ready?

- What is Redirection?

- What are Linux processes?

- a – How are Linux processes created?

- b – How are files stored on Linux?

- c – How are file descriptors used on Linux?

- What is Output redirection on Linux?

- a – How does output redirection works?

- b – Output Redirection to files in a non-destructive way

- c – Output redirection gotchas

- What is Input Redirection on Linux?

- a – How does input redirection works?

- b – Redirecting standard input with a file containing multiple lines

- c – Combining input redirection with output redirection

- d – Discarding standard output completely

- What is standard error redirection on Linux?

- a – How does standard error redirection work?

- b – Combining standard error with standard output

- What are pipelines on Linux?

- Conclusion

What is Redirection?

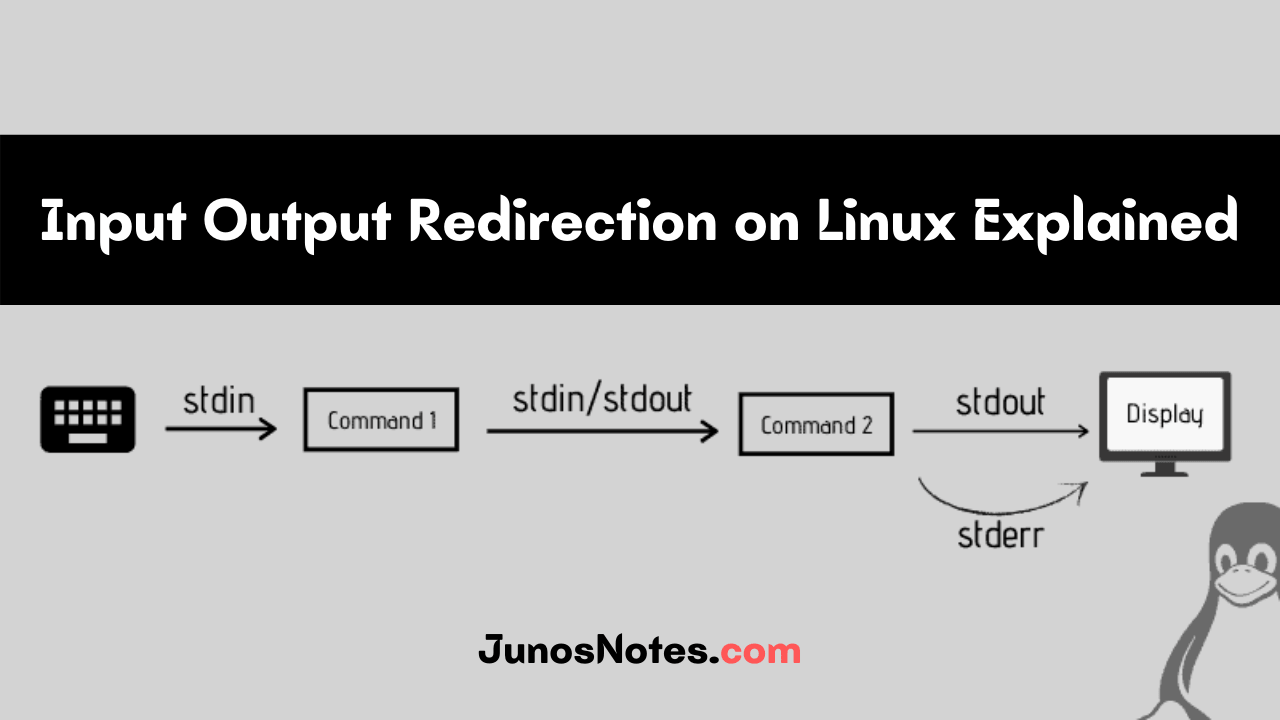

In Linux, Redirection is a feature that helps when executing a command, you can change the standard input/output devices. The basic workflow of any Linux command is that it takes an input and gives an output.

- The standard input (stdin) device is the keyboard.

- The standard output (stdout) device is the screen.

With redirection, the standard input/output can be changed.

What are Linux processes?

Before understanding input and output on a Linux system, it is very important to have some basics about what Linux processes are and how they interact with your hardware.

If you are only interested in input and output redirection command lines, you can jump to the next sections. This section is for system administrators willing to go deeper into the subject.

- Linux Tee Command with Examples

- Monitoring Linux Logs with Kibana and Rsyslog | Using Kibana and Rsyslog to monitor Linux logs

- How To Install Logstash on Ubuntu 18.04 and Debian 9 | Tutorial on Logstash Configuration

a – How are Linux processes created?

You probably already heard it before, as it is a pretty popular adage, but on Linux, everything is a file.

It means that processes, devices, keyboards, hard drives are represented as files living on the filesystem.

The Linux Kernel may differentiate those files by assigning them a file type (a file, a directory, a soft link, or a socket for example) but they are stored in the same data structure by the Kernel.

As you probably already know, Linux processes are created as forks of existing processes which may be the init process or the systemd process on more recent distributions.

When creating a new process, the Linux Kernel will fork a parent process and it will duplicate a structure which is the following one.

b – How are files stored on Linux?

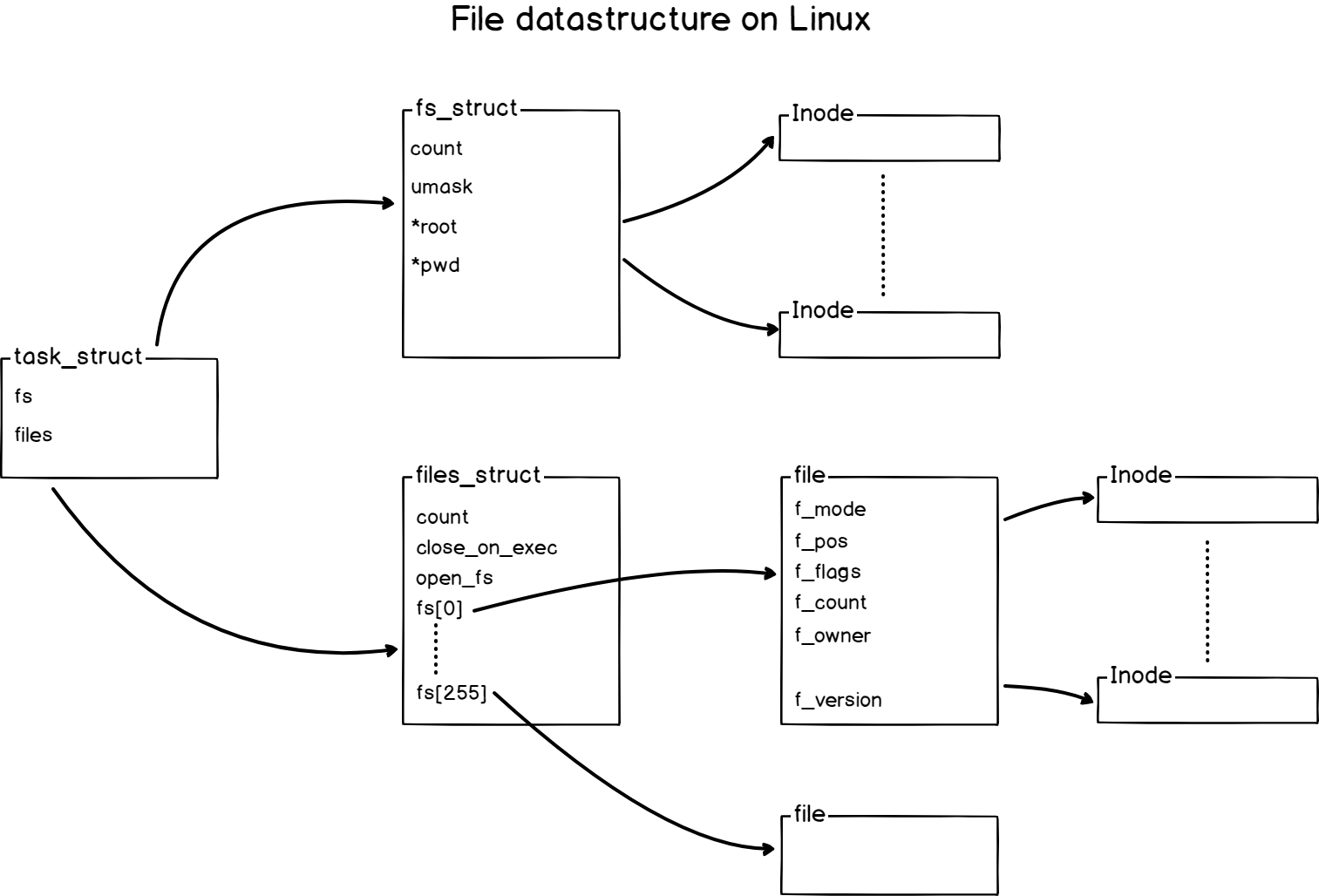

I believe that a diagram speaks a hundred words, so here is how files are conceptually stored on a Linux system.

As you can see, for every process created, a new task_struct is created on your Linux host.

This structure holds two references, one for filesystem metadata (called fs) where you can find information such as the filesystem mask for example.

The other one is a structure for files holding what we call file descriptors.

It also contains metadata about the files used by the process but we will focus on file descriptors for this chapter.

In computer science, file descriptors are references to other files that are currently used by the kernel itself.

But what do those files even represent?

c – How are file descriptors used on Linux?

As you probably already know, the kernel acts as an interface between your hardware devices (a screen, a mouse, a CD-ROM, or a keyboard).

It means that your Kernel is able to understand that you want to transfer some files between disks, or that you may want to create a new video on your secondary drive for example.

As a consequence, the Linux Kernel is permanently moving data from input devices (a keyboard for example) to output devices (a hard drive for example).

Using this abstraction, processes are essentially a way to manipulate inputs (as Read operations) to render various outputs (as write operations)

But how do processes know where data should be sent to?

Processes know where data should be sent to using file descriptors.

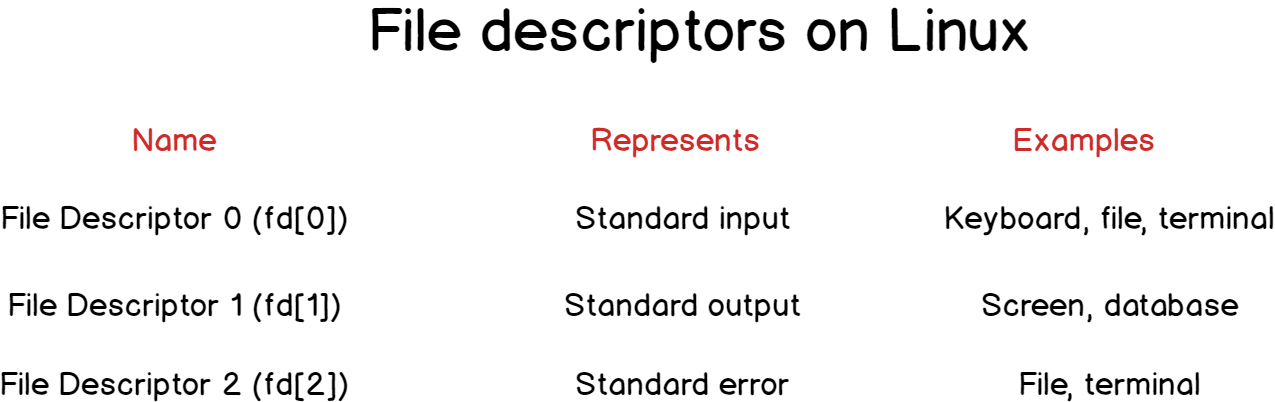

On Linux, the file descriptor 0 (or fd[0]) is assigned to the standard input.

Similarly the file descriptor 1 (or fd[1]) is assigned to the standard output, and the file descriptor 2 (or fd[2]) is assigned to the standard error.

It is a constant on a Linux system, for every process, the first three file descriptors are reserved for standard inputs, outputs, and errors.

Those file descriptors are mapped to devices on your Linux system.

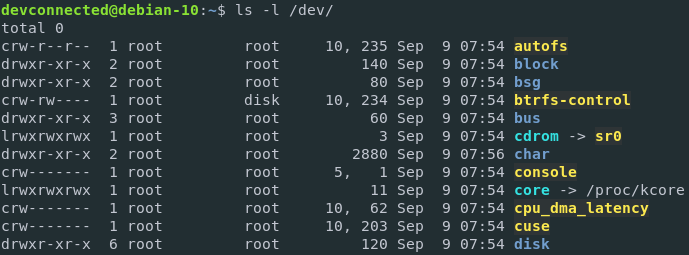

Devices registered when the kernel was instantiated, they can be seen in the /dev directory of your host.

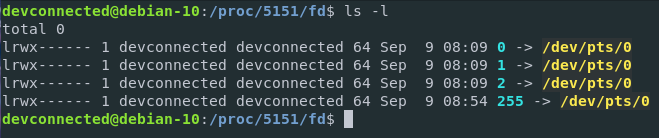

If you were to take a look at the file descriptors of a given process, let’s say a bash process for example, you can see that file descriptors are essentially soft links to real hardware devices on your host.

As you can see, when isolating the file descriptors of my bash process (that has the 5151 PID on my host), I am able to see the devices interacting with my process (or the files opened by the kernel for my process).

In this case, /dev/pts/0 represents a terminal which is a virtual device (or tty) on my virtual filesystem. In simpler terms, it means that my bash instance (running in a Gnome terminal interface) waits for inputs from my keyboard, prints them to the screen, and executes them when asked to.

Now that you have a clearer understanding of file descriptors and how they are used by processes, we are ready to describe how to do input and output redirection on Linux.

What is Output redirection on Linux?

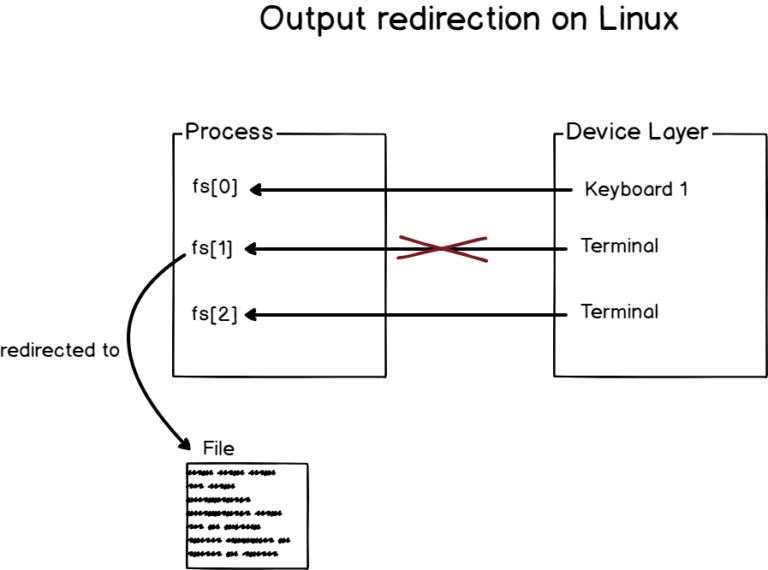

Input and output redirection is a technique used in order to redirect/change standard inputs and outputs, essentially changing where data is read from, or where data is written to.

For example, if I execute a command on my Linux shell, the output might be printed directly to my terminal (a cat command for example).

However, with output redirection, I could choose to store the output of my cat command in a file for long-term storage.

a – How does output redirection works?

Output redirection is the act of redirecting the output of a process to a chosen place like files, databases, terminals, or any devices (or virtual devices) that can be written to.

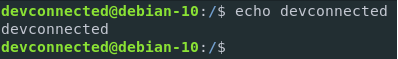

As an example, let’s have a look at the echo command.

By default, the echo function will take a string parameter and print it to the default output device.

As a consequence, if you run the echo function in a terminal, the output is going to be printed in the terminal itself.

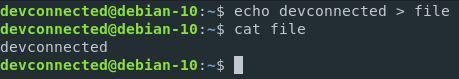

Now let’s say that I want the string to be printed to a file instead, for long-term storage.

To redirect standard output on Linux, you have to use the “>” operator.

As an example, to redirect the standard output of the echo function to a file, you should run

$ echo junosnotes > file

If the file is not existing, it will be created.

Next, you can have a look at the content of the file and see that the “junosnotes” string was correctly printed to it.

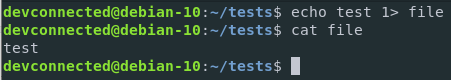

Alternatively, it is possible to redirect the output by using the “1>” syntax.

$ echo test 1> file

b – Output Redirection to files in a non-destructive way

When redirecting the standard output to a file, you probably noticed that it erases the existing content of the file.

Sometimes, it can be quite problematic as you would want to keep the existing content of the file, and just append some changes to the end of the file.

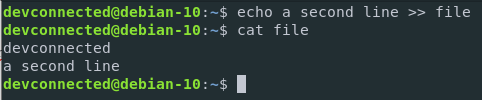

To append content to a file using output redirection, use the “>>” operator rather than the “>” operator.

Given the example we just used before, let’s add a second line to our existing file.

$ echo a second line >> file

Great!

As you can see, the content was appended to the file, rather than overwriting it completely.

c – Output redirection gotchas

When dealing with output redirection, you might be tempted to execute a command to a file only to redirect the output to the same file.

Redirecting to the same file

echo 'This a cool butterfly' > file sed 's/butterfly/parrot/g' file > file

What do you expect to see in the test file?

The result is that the file is completely empty.

![]()

Why?

By default, when parsing your command, the kernel will not execute the commands sequentially.

It means that it won’t wait for the end of the sed command to open your new file and to write the content to it.

Instead, the kernel is going to open your file, erase all the content inside it, and wait for the result of your sed operation to be processed.

As the sed operation is seeing an empty file (because all the content was erased by the output redirection operation), the content is empty.

As a consequence, nothing is appended to the file, and the content is completely empty.

In order to redirect the output to the same file, you may want to use pipes or more advanced commands such as

command … input_file > temp_file && mv temp_file input_file

Protecting a file from being overwritten

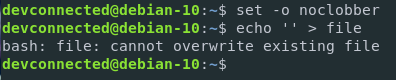

In Linux, it is possible to protect files from being overwritten by the “>” operator.

You can protect your files by setting the “noclobber” parameter on the current shell environment.

$ set -o noclobber

It is also possible to restrict output redirection by running

$ set -C

Note: to re-enable output redirection, simply run set +C

As you can see, the file cannot be overridden when setting this parameter.

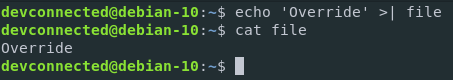

If I really want to force the override, I can use the “>|” operator to force it.

What is Input Redirection on Linux?

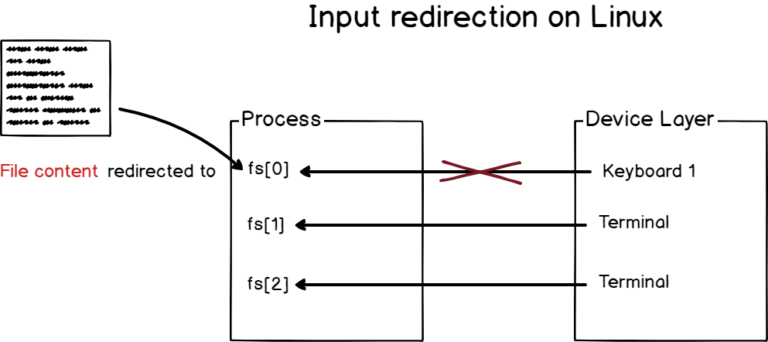

Input redirection is the act of redirecting the input of a process to a given device (or virtual device) so that it starts reading from this device and not from the default one assigned by the Kernel.

a – How does input redirection works?

As an instance, when you are opening a terminal, you are interacting with it with your keyboard.

However, there are some cases where you might want to work with the content of a file because you want to programmatically send the content of the file to your command.

To redirect the standard input on Linux, you have to use the “<” operator.

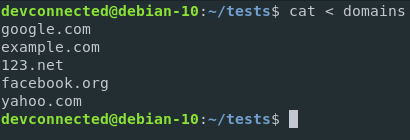

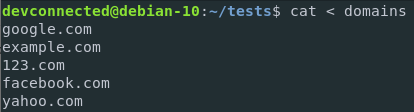

As an example, let’s say that you want to use the content of a file and run a special command on them.

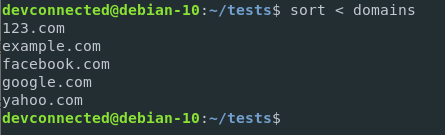

In this case, I am going to use a file containing domains, and the command will be a simple sort command.

In this way, domains will be sorted alphabetically.

With input redirection, I can run the following command

If I want to sort those domains, I can redirect the content of the domains file to the standard input of the sort function.

$ sort < domains

With this syntax, the content of the domains file is redirected to the input of the sort function. It is quite different from the following syntax

$ sort domains

Even if the output may be the same, in this case, the sort function takes a file as a parameter.

In the input redirection example, the sort function is called with no parameter.

As a consequence, when no file parameters are provided to the function, the function reads it from the standard input by default.

In this case, it is reading the content of the file provided.

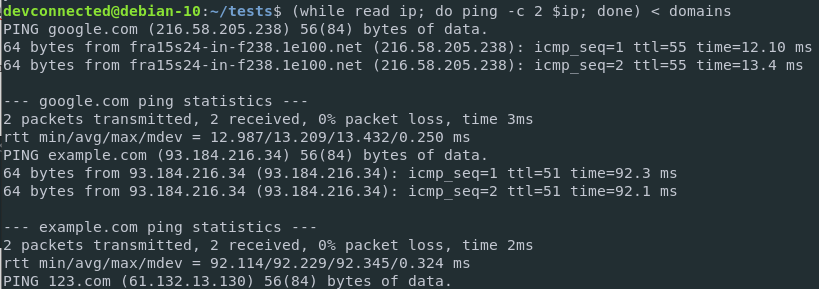

b – Redirecting standard input with a file containing multiple lines

If your file is containing multiple lines, you can still redirect the standard input from your command for every single line of your file.

Let’s say for example that you want to have a ping request for every single entry in the domains file.

By default, the ping command expects a single IP or URL to be pinged.

You can, however, redirect the content of your domain’s file to a custom function that will execute a ping function for every entry.

$ ( while read ip; do ping -c 2 $ip; done ) < ips

c – Combining input redirection with output redirection

Now that you know that standard input can be redirected to a command, it is useful to mention that input and output redirection can be done within the same command.

Now that you are performing ping commands, you are getting the ping statistics for every single website on the domains list.

The results are printed on the standard output, which is in this case the terminal.

But what if you wanted to save the results to a file?

This can be achieved by combining input and output redirections on the same command.

$ ( while read ip; do ping -c 2 $ip; done ) < domains > stats.txt

Great! The results were correctly saved to a file and can be analyzed later on by other teams in your company.

d – Discarding standard output completely

In some cases, it might be handy to discard the standard output completely.

It may be because you are not interested in the standard output of a process or because this process is printing too many lines on the standard output.

To discard standard output completely on Linux, redirect the standard output to /dev/null.

Redirecting to /dev/null causes data to be completely discarded and erased.

$ cat file > /dev/null

Note: Redirecting to /dev/null does not erase the content of the file but it only discards the content of the standard output.

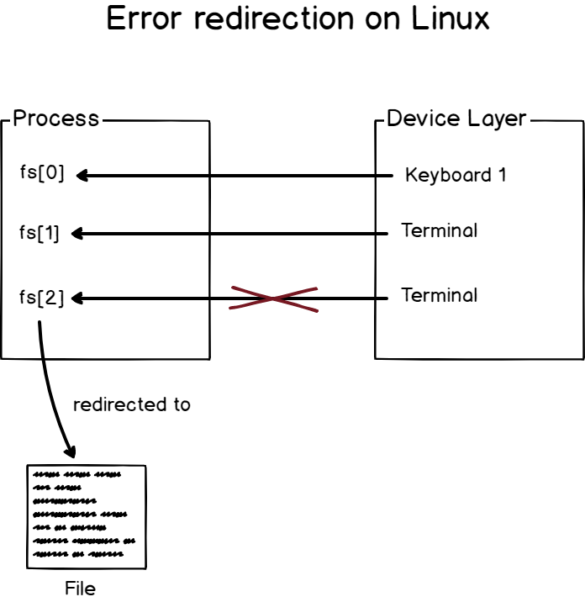

What is standard error redirection on Linux?

Finally, after input and output redirection, let’s see how standard error can be redirected.

a – How does standard error redirection work?

Very similarly to what we saw before, error redirection is redirecting errors returned by processes to a defined device on your host.

For example, if I am running a command with bad parameters, what I am seeing on my screen is an error message and it has been processed via the file descriptor responsible for error messages (fd[2]).

Note that there are no trivial ways to differentiate an error message from a standard output message in the terminal, you will have to rely on the programmer sending error messages to the correct file descriptor.

To redirect error output on Linux, use the “2>” operator

$ command 2> file

Let’s use the example of the ping command in order to generate an error message on the terminal.

Now let’s see a version where the error output is redirected to an error file.

As you can see, I used the “2>” operator to redirect errors to the “error-file” file.

If I were to redirect only the standard output to the file, nothing would be printed to it.

As you can see, the error message was printed to my terminal and nothing was added to my “normal-file” output.

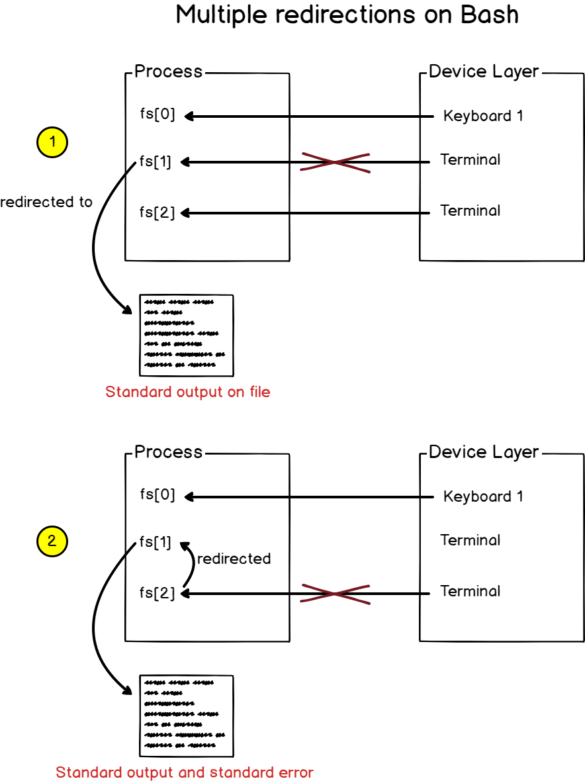

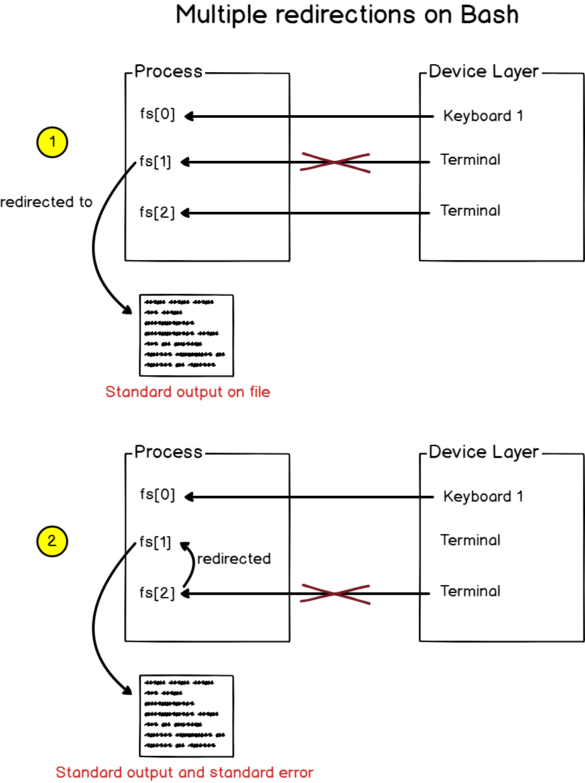

b – Combining standard error with standard output

In some cases, you may want to combine the error messages with the standard output and redirect it to a file.

It can be particularly handy because some programs are not only returning standard messages or error messages but a mix of two.

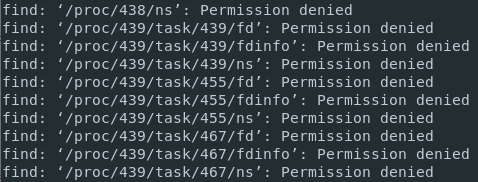

Let’s take the example of the find command.

If I am running a find command on the root directory without sudo rights, I might be unauthorized to access some directories, like processes that I don’t own for example.

As a consequence, there will be a mix of standard messages (the files owned by my user) and error messages (when trying to access a directory that I don’t own).

In this case, I want to have both outputs stored in a file.

To redirect the standard output as well as the error output to a file, use the “2<&1” syntax with a preceding “>”.

$ find / -user junosnotes > file 2>&1

Alternatively, you can use the “&>” syntax as a shorter way to redirect both the output and the errors.

$ find / -user junosnotes &> file

So what happened here?

When bash sees multiple redirections, it processes them from left to right.

As a consequence, the output of the find function is first redirected to the file.

Next, the second redirection is processed and redirects the standard error to the standard output (which was previously assigned to the file).

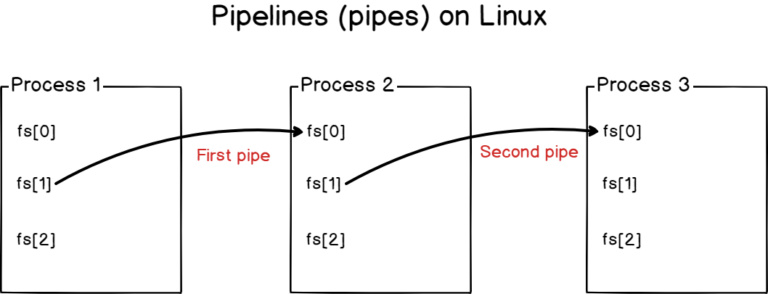

What are pipelines on Linux?

Pipelines are a bit different from redirections.

When doing standard input or output redirection, you were essentially overwriting the default input or output to a custom file.

With pipelines, you are not overwriting inputs or outputs, but you are connecting them together.

Pipelines are used on Linux systems to connect processes together, linking standard outputs from one program to the standard input of another.

Multiple processes can be linked together with pipelines (or pipes)

Pipes are heavily used by system administrators in order to create complex queries by combining simple queries together.

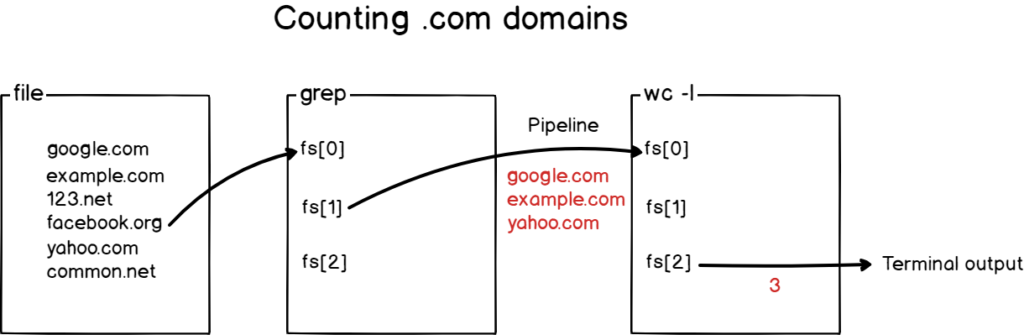

One of the most popular examples is probably counting the number of lines in a text file, after applying some custom filters on the content of the file.

Let’s go back the domains file we created in the previous sections and let’s change their country extensions to include .net domains.

Now let’s say that you want to count the numbers of .com domains in the file.

How would you perform that? By using pipes.

First, you want to filter the results to isolate only the .com domains in the file. Then, you want to pipe the result to the “wc” command in order to count them.

Here is how you would count .com domains in the file.

$ grep .com domains | wc -l

Here is what happened with a diagram in case you still can’t understand it.

Awesome!

Conclusion

In today’s tutorial, you learned what input and output redirection is and how it can be effectively used to perform administrative operations on your Linux system.

You also learned about pipelines (or pipes) that are used to chain commands in order to execute longer and more complex commands on your host.

If you are curious about Linux administration, we have a whole category dedicated to it on JunosNiotes, so make sure to check it out!